For an important sector of German large-scale industry, the law on employee codetermination in the mining, iron-making, and steel-making industry, which was passed on April 10, 1951, through a genuine parliamentary vote in the Bundestag of the Federal Republic, marks the realization of the demand made by our unforgettable Hans Böckler, who wanted to see employees elevated to the status of “economic citizens” and made into equal partners in the enterprises. The law only affects the coal and steel industry – but it thereby affects the crucial core of our entire economy. It is from these “commanding heights” that the economy is determined down to its smallest units. In the long run, it will prove impossible to limit employee codetermination to the coal and steel sector. The working class, which is closely united in solidarity over its own fate, will not be able to accept that the remaking of the social structure affects only the basic industries. In other words: the April 10th law has flung open the door for a new social order, but the struggle over its realization will end only when the constitution of society in all of Germany has been freed from the chains of capital’s domination over labor.

The Codetermination Law is indeed a bundle of paragraphs, but no one should deceive himself: with these paragraphs a revolutionary act has been carried out, a milestone has been achieved – on the third path to a new social order. Today, workers who have organized themselves in free unions throughout the entire world look to the German unions and their struggle for codetermination in the confident hope that the right of codetermination will lead us out of the dead end in which we find ourselves as a result of the alternative to capitalism – state socialism.

[ . . . ]

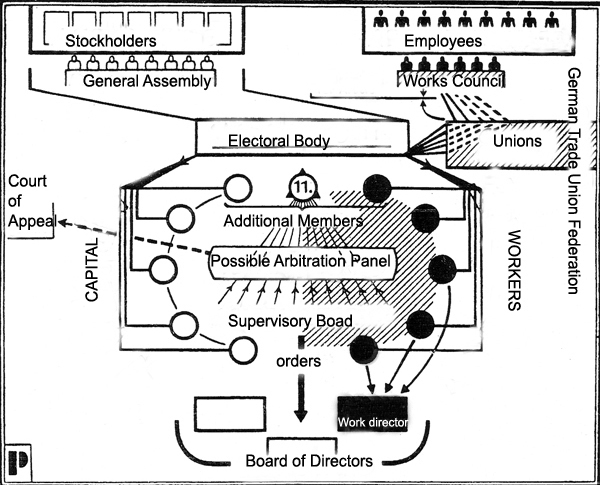

The paragraphs of the April 10th law stipulate (see our illustration at the end):

In the future, alongside five representatives of the stockholders (owners), five representatives of the employees will sit on the supervisory board and have a say in the fate of the given enterprise. The fifth representative on the stockholder’ side, however, may not a represent an employer’s association, nor may the fifth representative on the employees’ side represent a union. They are referred to in the law as “additional members,” to whom the hotly contested eleventh man also belongs. This eleventh man is supposed to be elected by the ten members of the supervisory board. If there is no direct election by the supervisory board, a mediation committee – composed of two board members each from the employers’ and the employee’s side – proposes three candidates for election to the electoral body, which is practically the same as the general assembly of the company. The electoral body can refuse this choice. At the request of the mediation committee, the relevant court of appeal [Oberlandesgericht] will decide on whether the reasons for the refusal are justified. If the court upholds the refusal, the mediation committee must present three more candidates to the electoral body.

Of the five employee representatives on the supervisory board, two, a company worker and an employee, will be proposed by the works council in agreement with the company’s leading unions and their top organizations. The Federal Minister for Labor decides when the unions and the works council cannot agree on two candidates for election. The three remaining employee representatives are proposed by the unions in agreement with the works council. The electoral body is bound by the recommendations of the unions and their top organizations.

The supervisory board elects a work director as an equal member of the managing board. He is considered elected if a majority of the employee representatives agree on him.

Source: Walter Pahl, Gewerkschaftliche Monatshefte [Union Monthy Journal] 2 (1951): 225 ff; reprinted in Christoph Kleßmann, Die doppelte Staatsgründung. Deutsche Geschichte 1945-1955 [The Founding of Two States. German History 1945-1955]. Göttingen, 1982, pp. 487-88.

Translation: Thomas Dunlap